Michele Mitchell

I pull up in front of an anonymous two story building near the river, the ugly old brick partially covered with plaster, as though one of its various occupants had started to improve it…and simply lost interest.

Don't get me wrong. As a refugee from the Big City, I'm rather partial to this kind of loft building - totally unprepossessing from the outside - an amazing universe within. I pause for a moment, in the blinding sunlight, wondering what awaits me, and then I hear Michele welcoming me, and I ascend the wooden steps to the second floor.

Here, the light pours in softly, illuminating what is clearly a functioning classroom. I should stop and ask about it, but I am already drawn to the art covered walls. It is immediately apparent that Michele Mitchell is a realist in the French Classical tradition.

"I'm part of a wonderful lineage," she explains. "From Master to Apprentice, from Boucher/Vien 1703-1770 to Jacque Louis David 1748-1825, then to Antoine Jean Gros 1771-1835 to Delaroche/Gleyre 1808-1874 (students of Charles Gleyre included Monet, Renoir and Whistler), then to Jean-Leon Gerome 1824-1904, to William McGregor Paxton 1869-1941, to R.H. Ives Gammell 1893-1981, to my teacher, Richard Lack 1928-present. And then I am next in line, with my contemporaries at Richard Lack's atelier."

An atelier is essentially a teaching studio, a workshop operated by a Master for a small group of students - in this case, a Master in the craft of picture making, who is part of the lineage of many preceding Masters. It was in this tradition that Michele became part of the classical continuum, a practitioner of the knowledge and craft carried from lifetime to lifetime, along with the understanding and the wisdom to commit to specific objectivity.

"Sarah" - 70" x 38" Mountain Air, NC

"In addition," she continues, "I'm directly connected to the Impressionist tradition…"

I'm frankly surprised, even I know the Impressionists broke way from the Classical school. The intention for the Impressionists, was to see the whole in relationship, without the separation of conceptual boundaries through the definition of line. In her own words, "It was a gift to have had the opportunity to be linked to both schools. The training endowed me with a balance, where the heart may dance but where the intellect and capacity of selection is still present in very pure form."

"We are given this framework of time to dance in. Existence awaits. I respond with humility, openness and appreciation, and allowed to see, to feel, to be completely intoxicated by life. And as the breath is given back, so my brush gives back like a dancer finding its steps but never feeling the floor. An invitation to dance with Existence, this is what is allowed to me. To me, painting nature is like dancing with the Divine."

As a diehard minimalist and defender of form and abstraction, I'm on shaky ground here, but on the other hand, I grew up in a city with a world-class museum and superb classical collection. One of my earliest art memories is the post-coital Cupid and Psyche, painted by Jacques Louis David, the leading French painter of the neoclassical era. Since the intention of that period was to raise human consciousness and promote virtue, I have to assume his slyly perfect rendition of the ancient myth was an acknowledgement of the enormity of the task.

We agree that the French were meticulous draughtsmen, that the intention of their discipline was to see shape accurately. She sees it a discipline for life itself.

"With the integrity of seeing well, one can be elevated to compose well. Once engaged in the dialogue with nature, one's choices are changed. Life demands honesty and integrity. With this as the means, what is revealed is something beyond concept, idea or imagination. And Life begins to sculpt the artist."

Like Psyche, I know I'm being seduced. It's impossible not to respond to her integrity and the way it is reflected in her work - these glorious still lives and portraits, fairly dancing with life and clearly done with a master's hand: a bright bowl of sunflowers set on a tapestry before a famous painting by Velàzquez; a woman in a hat, in ¾ profile, the calm acceptance in her face belied by the straining tendon in her neck; (The Call) - a fine rendering of our universal inner longing.

"I remember painting this and understanding the gift, that I was being allowed to respond to such a beautiful feeling…with color and line, hard edges and soft edges, a language of the eye that is connected to the heart."

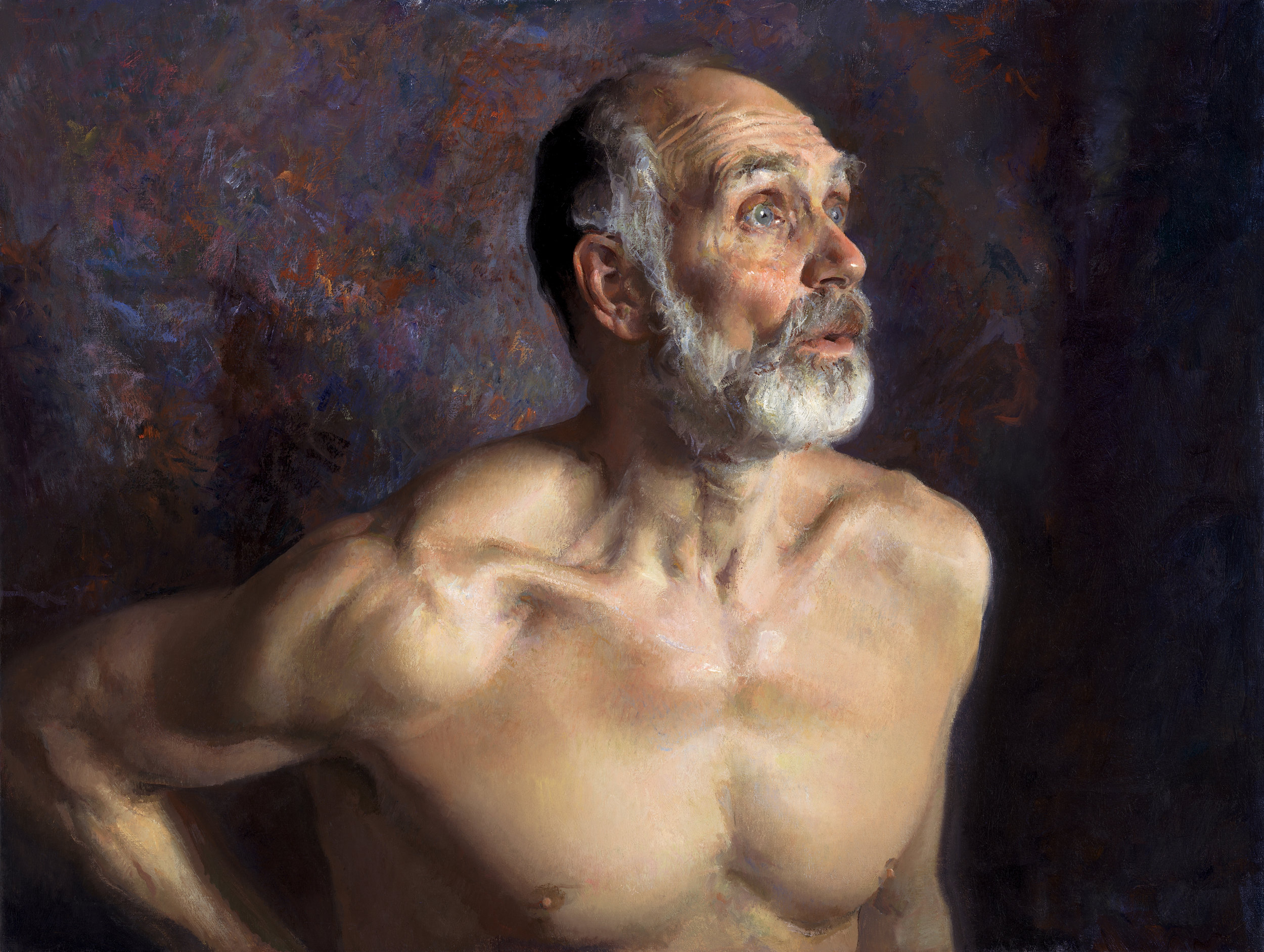

"Moving Towards the Light" 24" x 32"

Now we are standing in front of a painting entitled, Moving Toward the Light. A strained man, filled with effort and hope so individual, I'm convinced he looks familiar, and yet, so eternal he could as easily be biblical as contemporary. I resonate to his ephemeral pathos, the trap of having to live in body. I see it articulated in the tension of his naked shoulders, and his too bright stare of recognition.

"When I began this painting, I told him, "I need to find the commitment within you that I find within myself to be able to paint you."

She turns to me, now. "It's how I find the truth when I paint someone."

I feel my hackles rising. "The truth?"

"The one-on-one conversation... about love."

I suddenly flash on Kierkegaard's admonition, that "the crowd is untruth" - a concept that has apparently been waiting submerged, since my glory days in Philosophy 101, for this very Sunday - to hit me upside the head, and say "Now do you get it?"

"You certainly didn't learn to think this way in art school," I murmur.

"No, my heart was a great facilitator for wisdom. And I knew enough to trust my heart. I learned my truest friend and mentor was within."

Never the less, she's had a wonderful training. After a brief stint at the University of Illinois, she enrolled at the American Academy of Art in Chicago. She studied there for the next five years and traveled back and forth to Europe, producing a body of work, having shows, getting into galleries - in short, living her life as a fine artist. "But one day, I looked at what I was producing and realized my style was getting in the way of my art."

She's just thrown me another curve, but before I can react she continues, "When I speak of realism I speak of something pure, something true. You have to become transparent to be able to see what has been, and what is, and what will be - as a way of seeing the whole."

By this time, Michele's work was being shown, and she'd won a number of prestigious awards including two successive Society of Illustrators Exhibition Awards and Best of Show at the National Portrait Seminar International Competition. But in 1988, she enrolled at the Atelier Lack, Studio of Fine Arts in Minneapolis where she was brought into the French Classical tradition and taught how to see, "How to strike that balance between the heart and the head, how to engage in the kind of probing that leads to transparency, that allows one to see beauty in its clearest form."

"And the craft itself?" I ask.

"Craft is the tool. The fingers of the tradition. It links you to history, but your aspirations must be very specific."

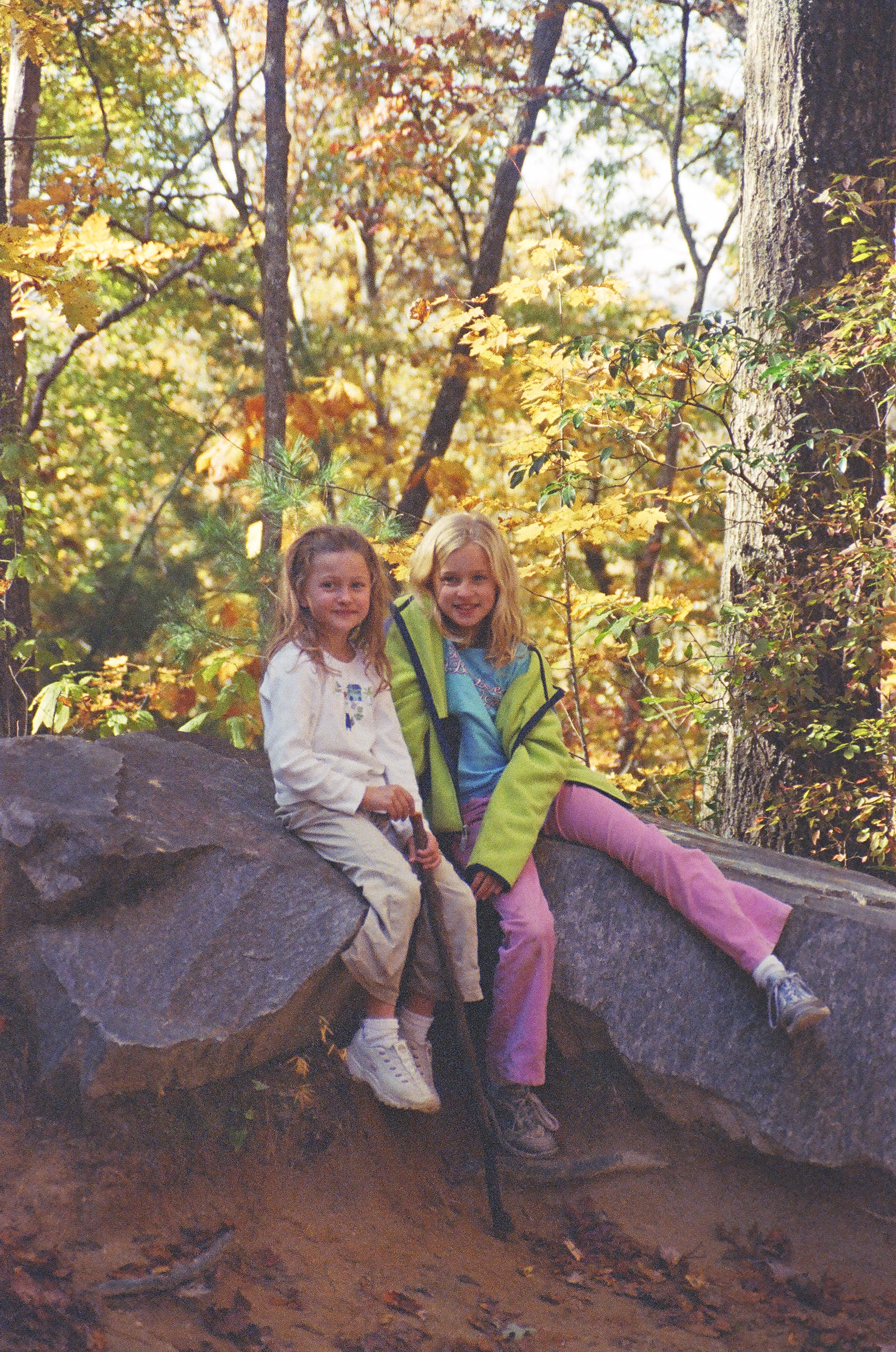

"Now I'm walking a journey I've never known - domesticity. When Jim and I came back from Florence with our daughter, Olivia, we learned that I was pregnant again and chose to stay in the States to give birth. We decided to move here from Chicago, where Olivia was born, to a place that promised to provide a culturally inspiring environment for the children and ourselves as artists." A month after arriving in Asheville, Maria Isabella (Bella) was born.

"Venus and Mars" 24" x 18"

"tuckered out from a day hike"

Now, Michele and her husband, Jim Ostlund, also a classically trained painter, have started their own atelier, to bring a classical foundation to children and to introduce the possibilities to the adults, who are interested in learning to see and articulate nature truthfully and equip them with the tools to do creative work.

In addition, since the birth of their daughters, who are now 7 and 5 years old, Michele and Jim have accepted portrait commissions, which has enabled them to provide a stable environment and to continue evolving within their craft. Not surprisingly, their work has been a strong response to their talent. For Michele, the reward is seeing a window start to open, that will allow her to pursue her personal work.

"I look forward to returning to the place where I may respond to the inspiration within me with complete abandonment, and allow my heart, with the voice as an artist, to find the means to dance with the Divine on canvas. To be an artist you are a part of life speaking of itself."

The portfolios of Michele Mitchell and Jim Ostlund may be seen by appointment at the Art Atelier, 375 Depot Street in Asheville. For more information about the Art Atelier, they may be contacted at theartatelier.com.

By Arlene Winkler

Article featured in Western North Carolina Woman, April 2005